Recently, KQED reporter Sarah Craig visited Salinas Chinatown to examine the connections between urban design (and the current revitalization initiative) and some of the pressing issues of the neighborhood: “isolation, violence, drug dealing, and prostitution.” She also said that she wanted to “emphasize the important history of the place.”

The resulting article and podcast in The California Report did indeed address the pressing issues, but little else. Craig conducted interviews and attended an ACE meeting. We suggested she consult our ACE Walking Tour website and its many resources on the history of Chinatown. Yet, in “Can Chinatown Design Its Way Out of Violence?” the neighborhood’s 124 years of history were somehow reduced to one long era of violence and vice.

Perhaps I should not be so surprised. Founded in 1893, Chinatown and its population of Chinese, Japanese, and Filipinos (and later, Mexicans and African Americans) has often been portrayed as a den of vice. John Steinbeck, Salinas’ literary father, portrayed it as such in East of Eden, and the image has stuck. The post-urban-renewal status of Chinatown as a locus of homelessness, drug-dealing, and murder doesn’t help, but it’s not the whole picture; in fact, it’s quite limited.

What of Chinatown’s past? Yes, there were pool halls, gambling parlors, and houses of ill repute; the two tong associations had a brief, but violent, rivalry that calmed down during the late 1930s; the nightlife was notorious, especially when soldiers from Fort Ord began to patronize the bars during and after WWII.

Why, then, does one of Craig’s interviewees, Jimmy Rice, say that Chinatown “used to be a really nice place”? I’ve heard this response a number of times, mostly from Chinatown old-timers. Perhaps they knew that there was more to the place than its sensational stories.

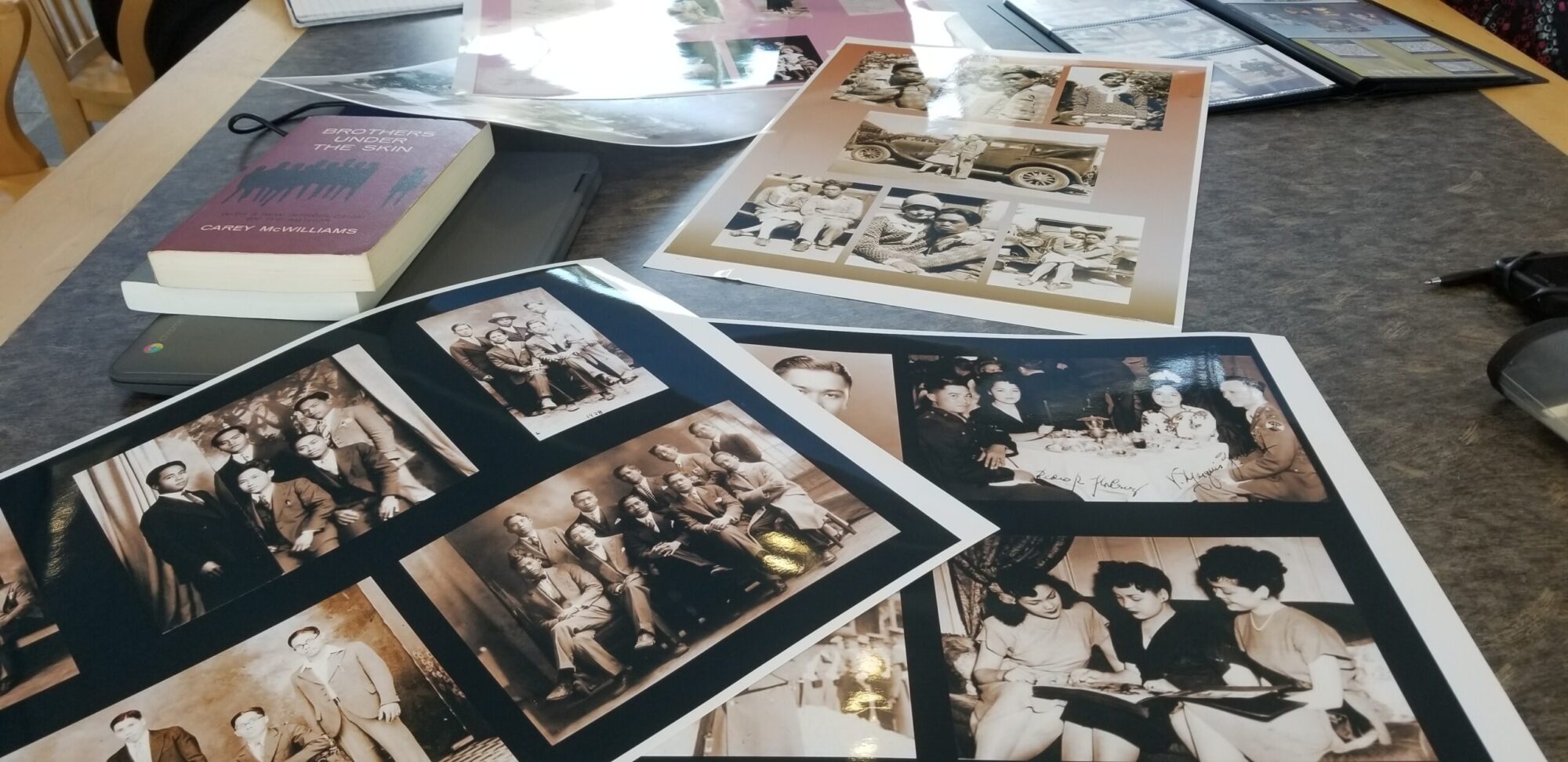

Chinatown was also children and families, homes, and hardworking parents who built up produce markets, dry-goods stores, restaurants, hotels, a photo shop, barber shops, a gas station, Filipino Community Center, and a Filipino Labor Union (F.L.U.) hall. There were labor contractors, lawyers, and a newspaper–the Philippines Mail–which became the longest running Filipino newspaper in the U.S.*

Spiritual needs were met in Chinatown, and buildings were erected to that end: the Japanese Buddhist Temple, a Chinese joss house (temple) to honor the ancestors, the Filipino Presbyterian Church, and the Confucius Church. These organizations also helped to educate the children of Chinatown, ensuring that they would not run loose on the streets after coming home from public school in town.

Chinatown children: photo from the Ahtye Family collection.

Moreover, Chinatown before and during WWII was a multicultural haven** for marginalized people who were not often tolerated in other parts of town unless they were there only to work. Ask any neighborhood old timer, and they’ll tell you that members of the ethnic groups who lived and worked in Chinatown, for the most part, got along. Perhaps they are glossing over the difficult parts; but for them, the revitalization of Chinatown is not entirely about gaining a future they never had. It’s also about remembering families and friends, and a place that they loved, a place where they once felt safe and at home, where they belonged.

It’s important to look squarely at the serious problems that plague Salinas Chinatown, and to work hard and collaboratively to alleviate the issues; however, we need to remember that Chinatown’s history is not so simple or one-sided. Even now, it seems, people forget that small, legitimate family businesses still operate in Chinatown, that it has always been multicultural–with neighbors including Mexican American and Black families and businesses–and services like Dorothy’s Place, Victory Mission, and health centers exist to help the homeless and others in need.

The Revitalization Plan [updated 2019 link] has been pursued so doggedly (this is the third attempt), in part, because another Chinatown still exists in the memories of those who grew up on its streets. They remember parents who migrated to the U.S., who struggled to build homes and businesses and educate their children. In their hearts, they know their neighborhood has always been, and can be, more than the sensational stories of violence and vice that continue to circulate. Along with dreams of two-way streets, connections to Salinas’ downtown area, new retail, restaurants, and a feeling of safety, they would also like to see a neighborhood that echoes the best of what they remember: a place that values the multicultural history and struggles of the families of Chinatown and retains its strong sense of community.

—Jean Vengua

*Founded in 1921 as The Philippine Independent by labor activists, Luis Agudo and D.L. Marcuelo, it went through several name changes; as the Philippines Mail, edited by Delfin Cruz, it lasted until the early 1980s.

**The sad exception, during WWII, was the experience of Japanese families, many of whom lost their properties and were interned as potential enemies of the State. Nevertheless, the Japanese Buddhist Temple has remained a strong bastion of community in Chinatown.

You must be logged in to post a comment.